What Does Ontario's Move to Merge Conservation Authorities Mean for Owen Sound & Grey-Bruce?

As Ontario overhauls its conservation system, questions emerge about what’s lost in the name of “efficiency,” and what it means for Grey Sauble’s future.

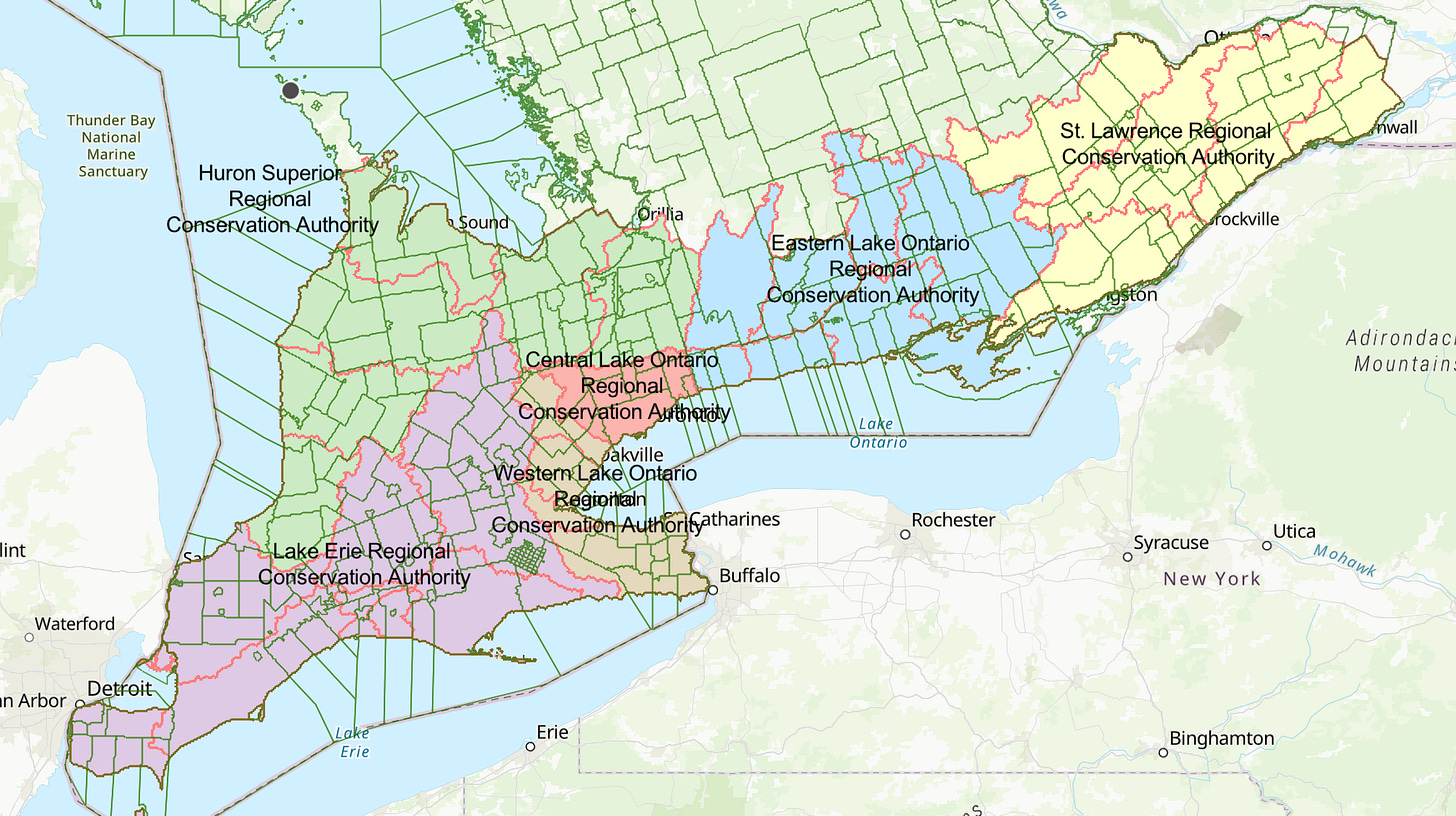

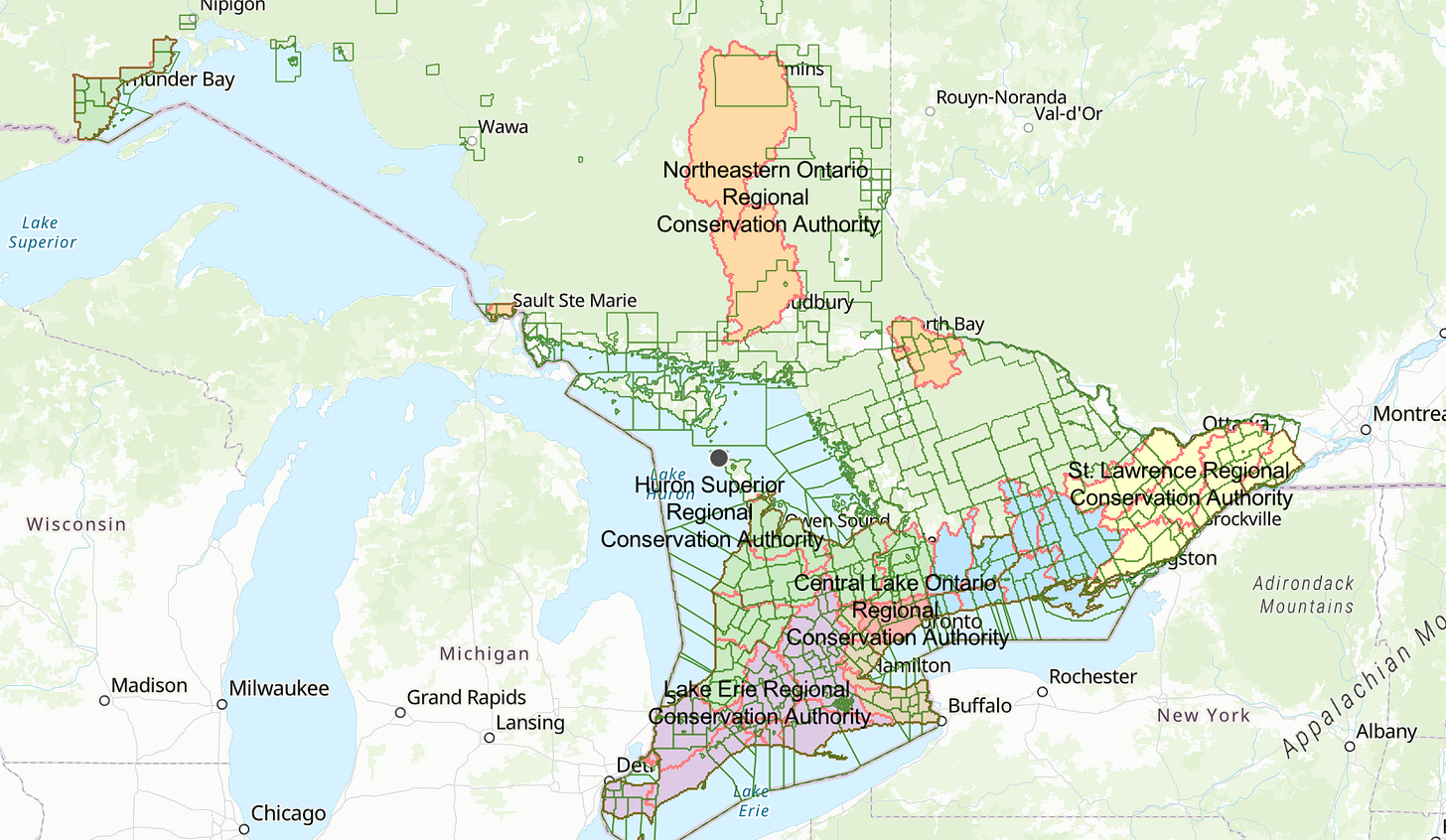

Ontario’s network of 36 conservation authorities is set for a major restructuring under a provincial proposal to consolidate them into seven regional bodies.

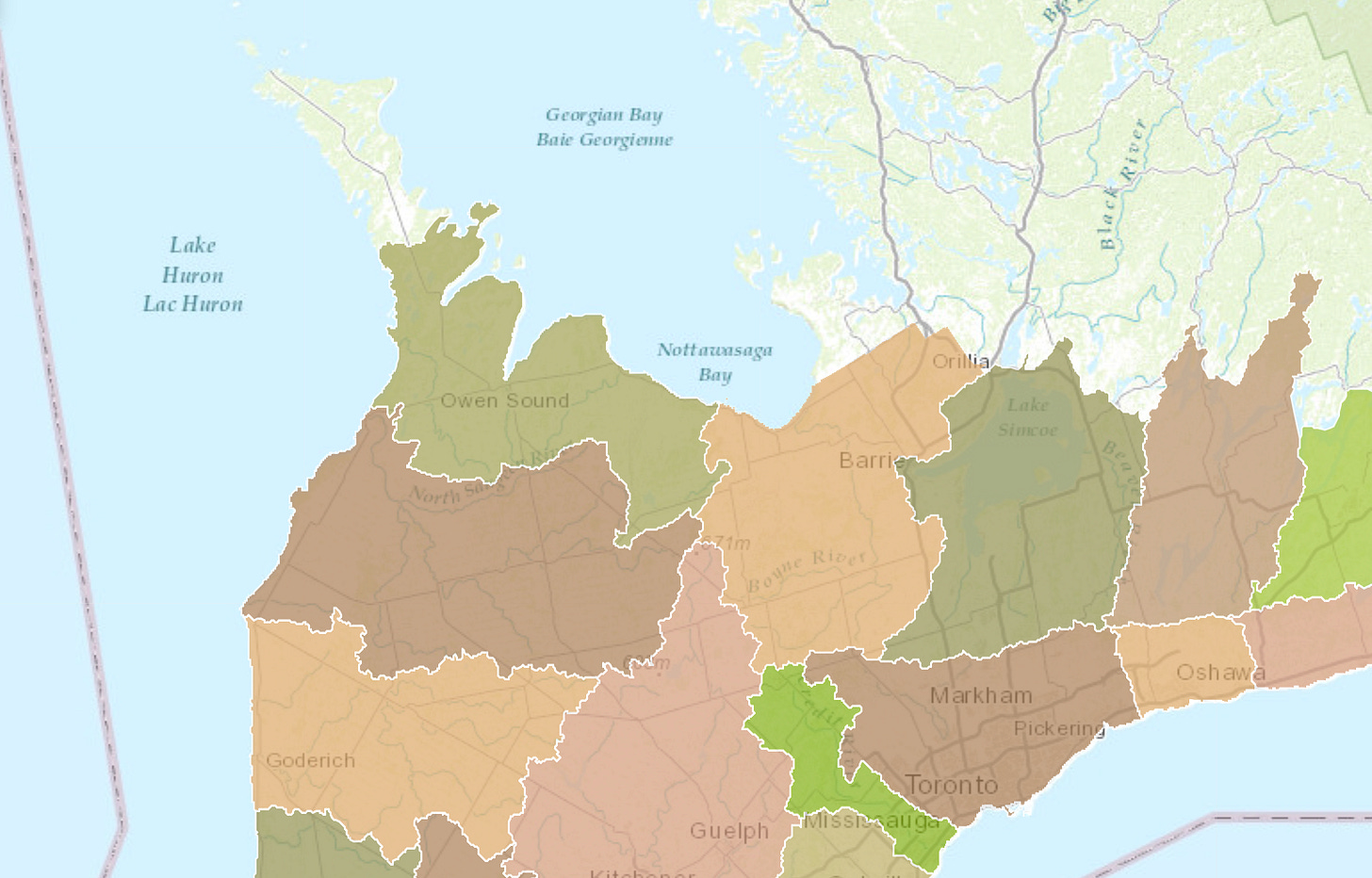

In Grey Bruce, the proposed changes would dissolve the Grey Sauble Conservation Authority and place Owen Sound and area within a new regional entity, the Huron-Superior Regional Conservation Authority.

Announced on October 31, the plan would centralize oversight under a new provincial agency — the Ontario Provincial Conservation Agency (OPCA) — tasked with streamlining governance, standardizing policies, and expediting permit approvals across watersheds.

The proposed Huron-Superior region appears to amalgamate the Grey Sauble, Saugeen Valley, Maitland Valley, Ausable Bayfield, Nottawasaga Valley, and Lakehead Region conservation authorities into a single unit, stretching from Thunder Bay to Barrie, based on watershed boundaries shown in the province’s interactive map.

Local Impact: Grey Sauble’s Future Unclear

The Grey Sauble Conservation Authority currently manages nearly 29,000 acres across an area of over 3,190 square kilometres, guided by a board composed of elected municipal representatives from eight local municipalities.

What happens to that local governance structure under the province’s plan? So far, the Ford government hasn’t said.

The Environmental Registry of Ontario posting includes no details on how local voices will be represented on the new regional boards, despite the geographic and demographic differences between Owen Sound, Tobermory, Barrie, and Thunder Bay.

Owen Sound Current has reached out to Tim Lanthier, CAO of GSCA, to ask whether the province has provided additional information about how regional representation might work. We’ll update our reporting if we receive a response.

We reached out to two local elected officials who have sat on the GSCA board as municipal appointees, as well. They declined to share their thoughts or concerns on the proposal.

Province Says It’s About Efficiency. Critics Call It Dismantling.

In its official notice, the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks claims the merger will “free up resources for front-line service delivery” and “reduce duplicative administrative costs.” The government says the current model is “fragmented,” leading to inconsistent standards and permit delays for builders, landowners, and municipalities.

But critics see a more troubling pattern. Since 2018, the Ford government has introduced a series of legislative changes that have stripped conservation authorities of key responsibilities—moves that environmental advocates say have already eroded the protections that helped Ontario avoid catastrophic flooding and environmental degradation for decades.

Prominent Canadian microbiologist Andrea Kirkwood told The Pointer, a GTA-based investigative publication, that while modernization may be needed, the scale of this consolidation amounts to “another death knell” for conservation authority mandates.

“What is ultimately being proposed is just another death knell to CA mandates and functions,” she said.

This proposed reorganization follows Bill 23, the More Homes Built Faster Act (2022), which barred conservation authorities from opposing developments in sensitive areas like wetlands, river valleys, and floodplains — even if those developments risk public safety.

The government also ordered CAs to identify “surplus” lands for potential housing development by the end of 2024.

Those changes were preceded by Bill 229 in 2020, which allowed the province to override conservation authority decisions using Minister’s Zoning Orders (MZOs) and required authorities to accept development applications in exchange for fees, even in areas where endangered species might be affected.

A System Built to Protect Ontarians from Disaster Now Being Undone

The modern form of conservation authorities and their flood mitigation powers were strengthened post-Hazel, the devastating 1954 storm that killed 81 people and caused widespread destruction in Toronto, although conservation authorities in Ontario were initially established under legislation from 1946.

The disaster led the province to give conservation authorities strong powers to prevent development in flood-prone areas, manage dams and reservoirs, and protect watersheds from future risk.

Now, experts worry that those safeguards are being steadily dismantled. Angela Coleman, general manager of Conservation Ontario, warned during legislative hearings that separating environmental protection from land-use planning would have serious consequences:

“It’s not the average day Conservation Authorities prepare for. We are planning for the 1:100 year flood, or larger storm,” she told a Standing Committee last year. “It’s the day the waters rise, when the roads are underwater, and the emergency vehicles must rescue people from their homes.”

The government insists its proposed changes will lead to faster permit processing and more “predictable” approvals for development projects. Yet Ontario recorded its lowest level of housing starts in a decade in 2024, casting doubt on whether deregulation is delivering results.

What Comes Next?

The proposal is open for public comment until December 22, 2025, at 11:59 p.m. Residents can submit feedback through the Environmental Registry of Ontario or by emailing ca.office@ontario.ca.

Some key questions the province is asking the public to weigh in on:

What are the key factors to ensure a successful transition to regional conservation authorities?

How should board governance be structured?

How can transparency and local input be maintained?

What benefits, if any, do you see in a regional approach?

For Owen Sound and Grey Bruce, the implications remain unclear: Will the region still have a voice in environmental decision-making? How will local issues be prioritized in such a vast regional structure?

And will consolidating authorities actually improve frontline service, or simply centralize control while weakening environmental oversight?

Those questions will need to be answered before legislation is introduced, expected in the coming weeks. The new regional model is scheduled to roll out between late 2026 and 2027.